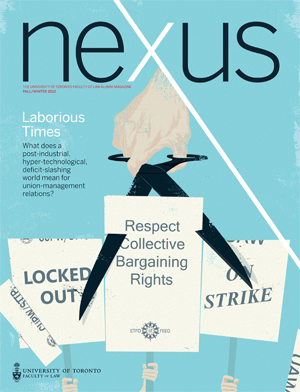

What does a post-industrial, hyper-technological, deficit-slashing world mean for union-management relations? The evolution of new labour laws.

What does a post-industrial, hyper-technological, deficit-slashing world mean for union-management relations? The evolution of new labour laws.

By Sheldon Gordon / Illustration By Oli Winward

“Solidarity forever, Solidarity forever, Solidarity forever,” rings out the hallowed workers’ anthem. “For the union makes us strong.”

But in 2012, not so much. It’s been a tumultuous couple of years for labour-management relations in Canada, and unions are feeling besieged.

The Canadian Auto Workers, anxious to avoid a crippling strike in the auto industry, submitted to four-year contracts with the Big Three auto makers that provide for annual bonuses, rather than wage increases, and a lower wage for new workers.

The federal government began laying off more than 19,000 workers as an austerity measure and used back-to-work legislation to pre-empt work stoppages—and collective bargaining—at Air Canada, CP Rail, Canada Post and Marine Atlantic.

Ontario’s government, in an effort to rein in its budget deficit, moved to impose a two-year wage freeze on its one-million public sector workers, starting with the province’s teachers.

This hard line toward organized labour came against a backdrop of a rapidly changing workplace, weakening union clout and a rightward shift in public opinion.

“In the U.S., and to some extent in Canada, you’re seeing politicians questioning the fundamental underpinnings of the labour model” that has defined labour-management relations since the 1930s, says Rhonda Shirreff, LLB 1999, of Heenan Blaikie LLP.

Public sector

In recent years, the public sector has been the stronghold of unionism in Canada. While 30 per cent of the Canadian workforce is unionized, only about 16 per cent of private sector workers are in unions vs. more than 70 per cent of public sector workers. Lately, however, federal and provincial governments have targeted these unions and their members.

The federal government, in the March 2012 budget, unveiled plans to cut the civil service by 19,200 jobs over the next three years through layoffs and retirements. The Public Service Alliance of Canada says more than 18,000 of its members have already received “workforce adjustment” notices.

At the provincial level, the Liberal government announced plans to impose a two-year wage freeze on Ontario’s public sector workers. It passed legislation imposing a collective agreement that, in essence, forbids teachers from striking during this round.

Governments at all levels have figured out that taking a hard line against public sector unions plays well with most voters, says John Monger, LLB 1989, of Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP. “There is a shift to the right generally in what the public seems to want. Governments feel they will advance their short-term interests by taking a run at ‘fat’ public sector employees, who, the man on the street has decided, are living better than he is.”

Labour has compared Ontario’s firm stance toward public sector workers to Wisconsin’s. (In 1959, Wisconsin was the first U.S. state to grant collective bargaining rights to public sector workers, but it stripped them of most of those rights in 2011.)

“Wisconsin was different in kind,” says Rhonda Shirreff, “because the state government was saying, ‘You no longer have a collective agreement. We’re not bargaining with you anymore.’ In Ontario, however, they’re just trying to change the bargain. We’ve seen it before [during the Bob Rae government’s Social Contract in 1993] and those changes didn’t gut collective bargaining.”

Elizabeth McIntyre, LLB 1976, of Cavalluzzo Shilton McIntyre & Cornish LLP, has dealt with intrusions into the collective bargaining process as far back as Pierre Trudeau’s wage and price controls under the Anti-Inflation Act. “It’s always triggered by difficult economic circumstances,” she says.

“Then, it was inflation. Now, in Ontario, it’s the deficit.” While these interruptions may not signal the end of collective bargaining, she says, “Historically, it has led not only to a lot of anger, but to a lot of litigation. Ten years after the Social Contract legislation, I was still doing litigation concerning it.”

Canadian unions are spooked by a trend in the U.S., where "right-to- work" legislation has spread to 24 states, denying unions the mandatory payment of union dues from workers—effectively making it virtually impossible for a union to sustain itself.

Private sector

There’s anger and litigation in the private sector, too. In the last two years, the Harper government has used back-to-work legislation—or the threat of it—to forestall or end strikes/lockouts at Air Canada and CP Rail (as well as at Crown corporations Canada Post and Marine Atlantic). Ottawa cited the potential harm to the “fragile economy.” The government asked the Canadian Industrial Relations Board (CIRB) to determine whether an airline such as Air Canada is an essential service.

Prof. Brian Langille, a labour law expert at the Faculty of Law, says the Canada Labour Code has a well-known test for essential services and the Air Canada case doesn’t meet that test. “Air Canada is not a public service nor is it a monopoly,” he says. “It is the view, across the board in the labour law community, that this doesn’t meet the statutory test of an essential service and that this intrusion into collective bargaining is completely unhelpful.”

Elizabeth McIntyre also doubts that the Harper back-to-work bills were about widening the definition of essential services. “If that’s what it is, it bears no relationship to how previous governments have dealt with essential services. They would normally allow the parties to work out in advance who are the essential workers.” She dubs Harper’s suppression of strikes a “Whack-A-Mole” response.

Damian Rigolo, LLB 1995, of Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP in Calgary disagrees, saying that the Harper government does indeed want a broadening of the definition. “This has a true philosophical underpinning,” he says. “But ultimately, they’ll have to amend the Canada Labour Code if they want a structured, entrenched change. I don’t think the CIRB will want to be the ultimate arbiter.”

The Rand formula

Canadian unions are spooked by a trend in the U.S., where “right-to-work” legislation has spread to 24 states, denying unions the mandatory payment of union dues from workers—effectively making it virtually impossible for a union to sustain itself.

In contrast, Canada’s Rand formula assures a mandatory union checkoff at the federal level and in the majority of provinces. The formula states that since all workers in a bargaining unit benefit when a union negotiates for them, it is reasonable to require them all to contribute a small amount towards the union’s costs.

In Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan, however, the conservative opposition parties now urge Rand’s repeal. Damian Rigolo says that if the U.S. right-to-work ideology “were to bleed into Canada, it could take hold in less unionized provinces. But it’s not on the very near horizon.”

Donald Eady, LLB 1988, of Paliare Roland, also doubts that Canadian provinces will turn into right-to-work jurisdictions. “Even in 1995, when Mike Harris led the most right-wing government Ontario has ever seen, he made changes to labour legislation but did not interfere with the Rand formula.” He points out that right-to-work legislation has been around in the U.S. for years without spreading to Canada.

The new workplace

Even if the Rand formula survives, however, technological innovation and globalization are radically changing the way work is performed and where it is performed. Some labour law practitioners believe the traditional approach to unionization has to be rethought.

It may be harder to organize when you have workers performing the same work in different ways and different places,” says Rhonda Shirreff. “Europe has a very different model than North America. You can have multiple unions in the same workplace, and workers can decide which union they wish to join.”

Prof. Langille says the traditional basis of labour law—“to protect vulnerable workers against the market power of employers”—needs to be supplemented with a more positive account. Labour law should no longer be viewed by management as “throwing sand into the wheels of the economy. There’s always going to be labour law, but the question is what kind of labour law do we want?”

“In the post-industrial, knowledge-based society, labour law should be conceived more as the law which structures the deployment of our most valuable asset—human capital—and not simply in terms of protecting workers,” Langille says. “Collective bargaining and employment standards law are more important than ever and need to be rethought. Consider pensions. In a world where people will increasingly work for more than one employer, it’s not sensible to link pensions to any particular employer because they become golden handcuffs, restricting employee mobility.”

Damian Rigolo also is convinced that, in a post-industrial workplace, the labour movement needs a different approach in how it recruits and represents workers. “A lot of employees will be working from home. How does a union represent those workers? How does it collectively bargain for them? And do those workers really want collective bargaining when they work in isolation or away from the traditional workplace?”

“I believe factors like those will lead to some type of re-evaluation,” he says, “but I don’t think that in the next 10 to 20 years there will be drastic overhauls in how unions operate. Just as employers may be a static entity, unions are, too. It’s tough to overhaul not only structural issues but philosophical issues of how a union works.”

A recent Abacus Data poll conducted for labour interests found a majority (53 per cent) of Canadians under the age of 30 say they would join a union if given the opportunity. That’s the highest level of any demographic surveyed.

Court rulings

Whatever the federal and provincial governments may do in specific interventions or with systemic laws, the rulings of the Supreme Court of Canada will also be crucial in determining the extent and character of collective bargaining.

Canadians are guaranteed the right to “freedom of association” under Sec. 2 of the Charter of Rights, but what does that actually mean? The high court interpreted that right somewhat differently in 2007 (B.C. health services) and in 2011 (Ontario farm workers).

“The Supreme Court of Canada case law is uncertain now as to how much, and to what extent, collective bargaining is a constitutionally protected activity,” says Bernard Fishbein, chair of the Ontario Labour Relations Board.

“It’s unclear where they’re going to go. The only certainty is that there will be more cases for them to comment on. Every time there’s a government intervention, the unions say they’re going to challenge it under the Charter.”

Interpreting the two landmark decisions, Rhonda Shirreff says: “In the 2011 decision, the Supreme Court may have created the possibility that other models could be considered.”

The next law to face a Charter challenge will be the Liberal government’s bill overriding the teachers’ bargaining rights, says Donald Eady. “Both the teachers’ unions and Canadian Union of Public Employees have challenged Bill 115 under the Charter.

“The Supreme Court of Canada said in its B.C. Health Services ruling that it’s important to consult with unions before you legislate [terms of employment], says Eady. “There was a form of consultation between the teachers’ unions and the government, but the government was very inflexible in the consultations.”

He adds: “The Ontario government also has a significant problem here in that they legislated in advance of allowing collective bargaining to work—as opposed to looking at the outcome of collective bargaining and saying as a government, ‘We can’t afford those outcomes.’”

New labour strategies

With employers drastically restructuring the workplace, unions are seeking new strategies. One such initiative is the forthcoming merger of the Canadian Auto Workers with the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union. The resulting entity will be the largest private-sector union in Canada, bargaining for 300,000 workers across 22 economic sectors.

The new union hopes not only to benefit from the shared resources of the unified workers (e.g., a bigger strike fund and more legal and research help) but also to organize people who have not previously joined unions, i.e., students, pensioners, the self-employed and the unemployed, as well as non-unionized workers such as contract staff or temps.

A recent Abacus Data poll conducted for labour interests found a majority (53 per cent) of Canadians under the age of 30 say they would join a union if given the opportunity. That’s the highest level of any demographic surveyed.

Representing pensioners would give unions more authority when bargaining on pensions and retiree benefits, says Donald Eady. As for students, if they are welcomed into a union, they might be more likely to consider joining one when they enter the work force. “Self-employed individuals could be offered a range of union benefits that might not otherwise be available to them,” he adds.

Faced with more difficult organizing conditions, unions need greater access to communicate with employees, Elizabeth McIntyre says. She cites the recent success of her client, the Ontario Nurses’ Association, in certifying two hospitals, one in Mississauga, the other in London.

“Under the Public Sector Labour Relations Transition Act, the union was able to put up information stands on the premises and do more public campaigns,” she says. “Because these were both hospital mergers, the union wasn’t limited—as unions usually are—to communicating with one employee at a time.”

It’s even more important for workers to exercise their right to bargain collectively today than it was in the past, says McIntyre. “Trade unions have always played a role in setting decent wages and benefits for workers. Today, however, the middle class is disappearing.”

No less an authority than Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of Canada, made that point last August when he told the CAW convention that “labour's share of national income is now at its lowest level in half a century across most advanced economies, including Canada.”

As the labour movement looks ahead to an uncertain future, it’s clear that reversing that trend will take more than a robust rendition of "Solidarity Forever."