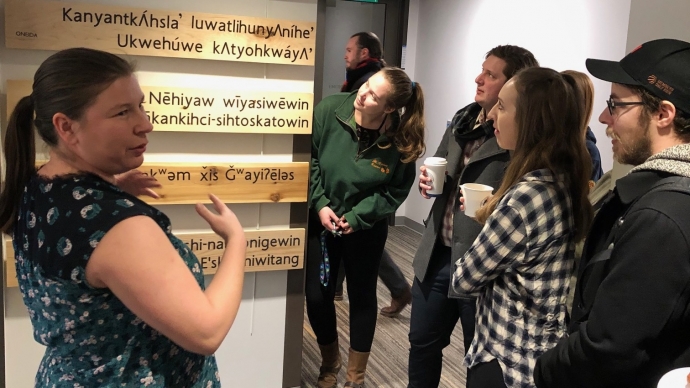

Rochelle Allan, left, acting manager of the Indigenous Initiatives Office, views the language installation with U of T law students

2019 is the United Nation's International Year of Indigenous Languages

Story and Photos by Lucianna Ciccocioppo

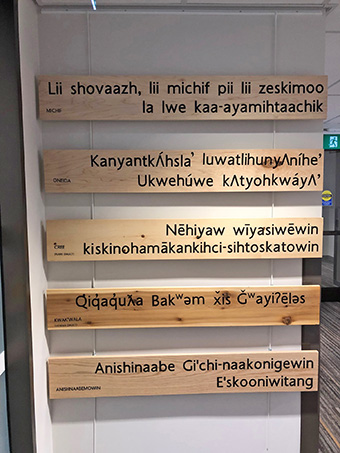

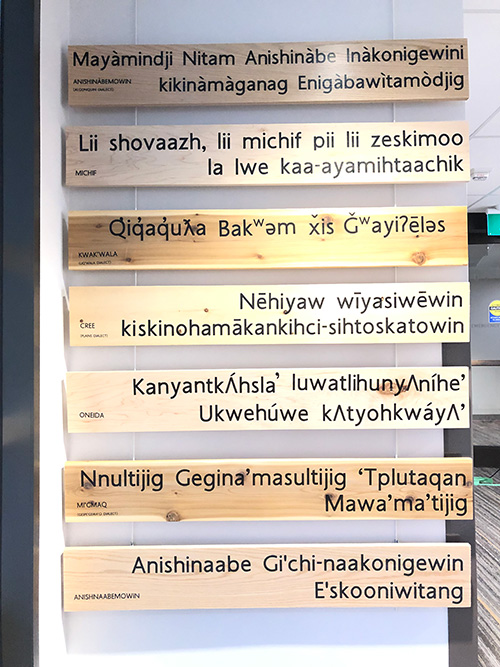

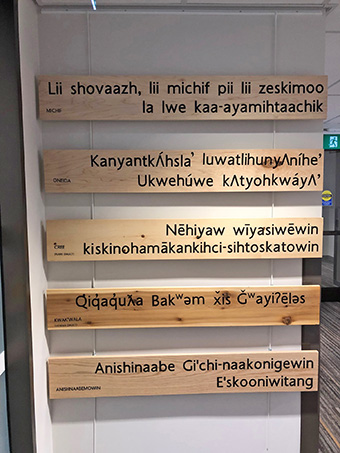

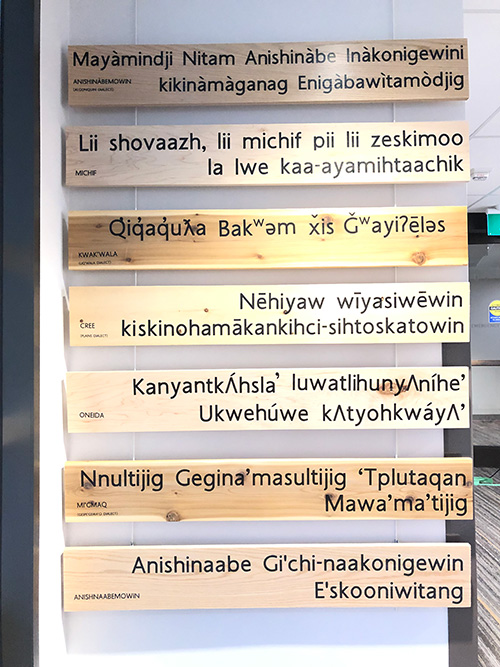

Five long, horizontal wood plaques with crisp black lettering are now displayed one above the other on a Student Services area wall in the Jackman Law Building at the Faculty of Law. It’s a language art project produced by the Indigenous Law Students Association, together with alumna Amanda Carling, who is on leave as manager of the Indigenous Initiatives Office (IIO), and Rochelle Allan, currently its acting manager.

Each plaque displays the name 'Indigenous Law Students Association,' in font type Aboriginal Sans, in the Michif, Oneida, Cree, Kwak’wala and Anishnaabemowin languages. They are made of different types of wood, such as pine, oak, cedar and maple, to reflect the trees native to the Indigenous community the language represents. And there is plenty of wall space to add more language plaques, as the Indigenous law students’ community grows and changes each year.

“A lot of us didn’t grow up around these languages and have very complicated relations with that, so representation, seeing it in places and hearing it spoken can be very emotional,” said Allan, after she acknowledged the traditional land with a statement (see below) that she read in Anishnaabemowin. "This installation is really great, but it’s a small piece of 100 years of work by Indigenous people to protect, preserve and to resist all of the powers that be within this territory who have tried to erase us for so long.”

The installation was unveiled January 25, to mark the International Year of Indigenous Languages, as proclaimed by the United Nations.

Law student Conlin Delbaere-Sawchuk, who is Métis, said language representation in the law school “is part of our commitment to bringing Indigenous issues to the forefront, particularly in law, and it serves as a reminder that these languages, like the people, are alive and well.”

Indigenous Law Students Association (ILSA) language plaques; Rochelle Allan (front left) with students in the ILSA, and alumnus John Borrows (in the last row, right)

Associate Professor Douglas Sanderson, an alumnus and a member the Beaver Clan of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, said reconciliation is about taking major steps forward, but he stressed small steps are important too.

“At the law school we often see Indigenous culture at the point of conflict with the law, but in the background I’ve been working to try to have Indigenous culture present, not just in the case law, but to hear our languages in the hallways, and hear the drums, and smell the sweetgrass and see the signs with our writing...So getting used to hearing those sounds and singing those songs is a step in growing together as a culture, and as a people, and it’s how we will achieve reconciliation.”

Traditional Indigenous foods, such as bannock, were served in a celebratory lunch for everyone as part of the unveiling

Alumnus John Borrows, an academic from the University of Victoria Law School who is currently here to teach an intensive course, said he was very pleased to see what was happening and what was being honoured with the installation. Borrows is Anishinaabe from the Cape Croker community in Ontario’s Bruce Peninsula.

“Language is life,” said Borrows. “The ways to understand who we are and what’s possible are formulated by our relationship with language. And those languages are formed by the ecologies that we’re from. So as we revitalize language, we find ourselves understanding more about the natural world of which we’re a part in Algonquin Haudenosaunee language groups.”

Borrows went on to say he was happy to understand the various languages the speakers spoke in their remarks, something he had to learn as an adult while teaching at the University of Minnesota law school, home to three academics who spoke and taught Anishnaabe.

“The work I am seeing here, and up and down the walls as eventually others will be added, is a very exciting thing...and warms my heart.”

The installation was unveiled January 25, to mark the International Year of Indigenous Languages, as proclaimed by the United Nations.

The IIO and ILSA are grateful for the knowledge and assistance of language keepers Bakuemgyala Language Group, Albert Owl, Olive Elm, Dale McCreery, Grace Zoldy, Leona Mitsuing. In addition, Rochelle Allan is grateful for the language speakers who assisted the Art Gallery of Ontario in developing this acknowledgement in Anishnaabemowin.

Maanda aki gii-dibendaanaawaa giw Huron-Wendat miinwaa Petun Nitam Anishinaabeg. Seneca miinwaa dash gwa Anishinaabeg Desnaang teg bezhig emkwaan wampum gchi-pizowin nendmoowin aawan maamowi sa nji gonda Naadek ezhi-maamowiziwaad miinwaa dash Anishinaabe Nswi Ishkoden debendgik ji-mina-maamowi nakaazong miinwaa ji-maamowi gnowenjigaadeg kina gegoo eteg gaataaying Gchi-gmiing.

Gchi-oodenaang gewii zhi-naaknigaade nji sa maanda gchi-kwiinwin ezhnikaadeg nji sa gchi-gimaanaang oodi Canada miinwaa dash gewii Mississaugas oodi Credit, ezhi-kenjgaadeg wi sa Gchi-oodenaang giishpinajigewin. Gchi-oodenaang pane gii-aawan gaa-nji-aash-toon-geng nji sa ntam Anishinaabeg.

In spring of 2019, two more plaques were added: in Anishinàbemowin (Algonquin Dialect), made of oak wood, and in Mi'gmaq (Gespe'gewa'gi dialect), made of cedar.