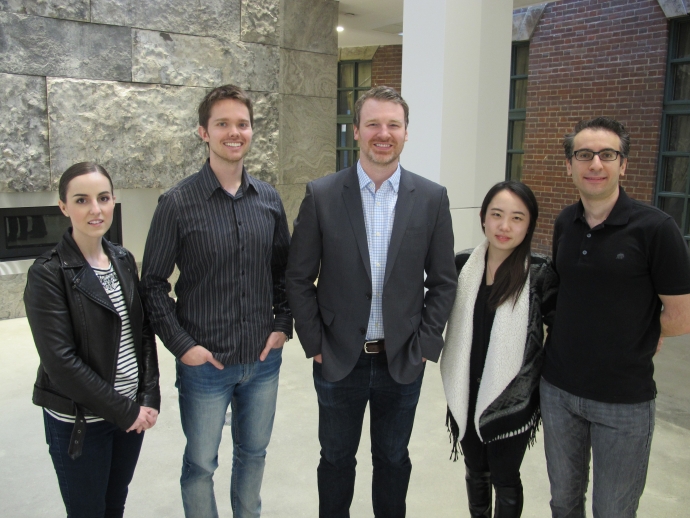

Pushing the boundaries of patent law: (left) Kerry Andrusiak, Damian Rolfe, adjunct professor and alumnus Max Morgan, Jenny Yunjeong Lee and Ahmed ElDessouki are some of the recent clinic participants.

By Peter Boisseau / Photography by Lucianna Ciccocioppo

Ingenious legal concepts created by University of Toronto law students, faculty and alumni are unleashing the power of the world’s leading open-access drug discovery institution to accelerate medical breakthroughs for the public good.

The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) is a public-private partnership based at U of T and Oxford University that aims to catalyze drug discovery by freely sharing the results of its research on the human genome, with no patent protection.

Faculty of Law students participating in the ground-breaking institution’s externship clinic may have found a way to deal with the SGC’s thorniest problem: How to ensure the thousands of scientists making free use of the unique “chemical probes” the consortium distributes also share what they themselves discover, based on the molecules they received.

Recently, students at the clinic teamed with adjunct professor Max Morgan, JD 2005, to create a “completely novel” material transfer agreement for the probes.

“The agreement itself provides that when the molecules are shared, the recipient becomes a trustee,” says Simon Stern, a U of T law professor and co-director of the Centre for Innovation Law and Policy, which offers the clinic. “That is a novel way of framing it, and I think it is a fascinating idea, with a lot of potential.”

Faculty of Law students participating in the ground-breaking institution’s externship clinic may have found a way to deal with the SGC’s thorniest problem: How to ensure the thousands of scientists making free use of the unique “chemical probes” the consortium distributes also share what they themselves discover, based on the molecules they received.

Law student Jenny Yunjeong Lee, who worked on the trust agreement, says the SGC’s unconventional mission to promote open-access research makes the clinic experience very special.

“I like the way the SGC externship program grabs the negative side effects the patent-based incentive system creates and finds entirely new legal relationships to promote faster scientific development,” says Lee.

With its university roots and altruistic vision of creating a “drug discovery ecosystem” where science and the public interest trump institutional and commercial gain, the SGC’s network now includes eight global pharmaceutical companies that help fund the consortium.

The SGC is “truly changing the innovation paradigm in drug discovery,” says Morgan, who helped start the clinic two years ago along with Stern and Aled Edwards, the consortium’s director and CEO.

“And the clinic externship program has made significant contributions to the SGC’s mandate,” adds Morgan, an intellectual property lawyer at Grand Challenges Canada.

Stern says the material-transfer agreement students helped craft to safeguard the SGC’s open-access mission is one example of how they are being exposed to a whole new perspective on patent law.

“We tend to teach from the perspective of using the law to protect intellectual property,” he notes. “This clinic is so appealing to us because students get to see how the alternatives work, which is a great thing to expose them to while they are on their way to becoming lawyers.”

Besides the role they played in developing the novel material-transfer agreement, students have been instrumental in other key legal work for the SGC, such as helping the consortium negotiate a new funding agreement with its pharmaceutical industry and non-profit partners.

They also assisted the SGC to incorporate a Canadian not-for-profit entity and registered charity, to help the organization secure additional sources of funding.

“It’s a really interesting nexus of opportunities,” says Edwards, the U of T molecular geneticist seconded to the SGC to manage the international consortium.

“These students and their supervisors have helped us negotiate with pharmaceutical lawyers to codify what we’re trying to put in place, and I think the students have, in turn, learned a lot of practical stuff,” he says.

“At the same time, the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Law have been able to combine to do something truly innovative in addressing a problem that is unique on both sides.”

Clinic law student Ahmed ElDessouki says the natural human inclination to share information has been restricted by otherwise well-intentioned patent laws, and pharmaceutical companies now realize the negative impact that can have on the time and cost involved in developing new medicines.

“What’s really unique about the clinic is learning how to align the interests of different stakeholders by coming up with creative solutions that benefit everyone,” says ElDessouki, who will be joining Smart and Biggar, a firm heavily involved in pharmaceutical patent work.

Fellow law student Kerry Andrusiak agrees, adding that without her experience at the clinic, she would never have considered different ways of pursuing protection for intellectual property.

“I think this is definitely the way that pharmaceutical industry research is moving,” says Andrusiak, who plans to work in the IP sector.

A growing body of evidence supports the SGC’s contention that patents encumber the speed of progress and discovery in drug research, especially when it comes to the less well-studied areas of the human genome, which the consortium focuses on explicitly.

Approximately 70 per cent of the world’s drug and biology research is done on just 10 per cent of the genes in the human body.

For his part, Edwards says one of the best experiences with the law students, alumni and faculty involved in the clinic has been the opportunity to not only brainstorm with scholars and practicing lawyers, but also young people, because of the different perspectives they bring.

Former clinic student Damian Rolfe, JD 2015, says those discussions challenged him to “dig deep” and think about the different contexts where the SGC could best use open innovation outside of the patent law system.

“We were thinking about the patent system in a very different way at the SGC,” says Rolfe, who is now articling with patent firm PCK IP.

Zarya Cynader, JD 2013, an intellectual property lawyer at Gilbert’s LLP, says one of the great things about working at the clinic was being able to engage with faculty members who share her interest in the intersection of biotechnology and law. It also brought back fond memories of her days as a law student.

Says Cynader: “Getting hands-on experience in a law clinic was my favourite part of law school, so I find it very rewarding to be able to help expand the experiential learning opportunities for students coming through the faculty today.”