Alumni discussed impact of the 2012 "pentalogy", five key SCC decisions

By Vito Cupoli

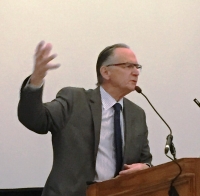

Prof. Ariel Katz

“It’s time to grow up and become copyright adults,” said Ariel Katz, SJD 2005.

The associate professor and Innovation Chair in Electronic Commerce at the Faculty of Law issued his challenge at the Copyright Canada Conference 2015, held Oct. 2nd, and sponsored by the Bora Laskin Law Library and the University of Toronto Library’s Scholarly Communication and Copyright Office.

Katz pointed to July 12, 2012 as the exact date when users of copyright should have at least begun to grow up. On that day, the Supreme Court of Canada issued five decisions in five separate cases regarding copyright. Together these cases are referred to as “the pentalogy”

The Court’s decisions have resulted in a period of timid adjustment where confusion about the the judgments has resulted in lost opportunities for users and creators of copyright-protected works alike. Some maintain the pentalogy amounted to an earthquake for copyright in Canada.

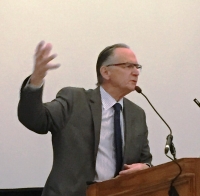

Not so, said Justice Ian Binnie, LLB 1965, who opened the conference with an emphatic rejection of how copyright reform has been portrayed by some.

“There is no seismic shift. The pentalogy didn’t shake the foundations of copyright law.”

If anything the Court was acting within its tradition, according to Prof. Katz. “If you take a longer, historical view, then the Supreme Court didn’t do anything revolutionary. It [the pentalogy] is actually much more in line with the tradition of copyright in Canada,” which has long protected use by the public.

Justice Ian Binnie

Justice Binnie, who retired from the Supreme Court in 2011 after a career of deciding and litigating copyright cases among many other topics, says the Court’s decision-making in the pentalogy was rooted in a perennial concern: “Where is the proper balance between creator rights, who should be properly compensated for what they have created, on the one hand and the interests of the broader community, freedom of speech, freedom of discussion and the commons on the other?”

Consumers who stream music and home video products can be forgiven for thinking that copyright issues in Canada are settled. For personal home use the boundaries are clear: purchase the right to consume and share music, video and books or be subject to the system set up by producers and distributors to catch those who view without paying or who pirate material protected by copyright.

Yet the world of educational and scholarly publishing, a focal point at this conference, has no such clarity when making and paying for paper copies of copyright material for use in classrooms and other non-commercial settings.

“There is no seismic shift. The pentalogy didn’t shake the foundations of copyright law.”

If this sounds like an obscure issue, consider that in Grades K-12 alone, approximately 10 billion pages of material are copied in Canadian schools every year outside of Quebec. Tens of millions of dollars are at stake and so is the quality of materials available for teaching.

It is equally important for the Faculty of Law and the University of Toronto to optimize their copyright practices for both users and creators. After all, the U of T is a behemoth in the copyright world, with the third-largest library system in North America. Its population of students and faculty, continually writing and publishing, make it the largest author organization in Canada. And after Harvard University, the University of Toronto is the largest producer of academic literature in the world, based on total publications and citations.

As a result of the court’s decisions, users of copyright works, such as those copied for a classroom, don’t have a checklist of rules to govern whether they may use a work. Instead they have six guidelines for how to apply the concepts of “fair dealing and reasonable use.” These terms offer a great deal of latitude when making a case for free use or for payment.

This transition to a system where each instance of copying must be decided on its own unique merits has been uncertain. Confusion about what is allowed has been widespread. Even very prominent users of copyright such as the CBC and the Toronto District School Board are operating on strict but out-of-date standards which blatantly ignore the flexibility of use allowed by Canadian law.

Katz said the new standards are not difficult to use and in fact, the pentalogy has put users in a very good position to make fair and reasonable use of copyrighted material regardless of whether they realize it. He urged conference audience members to be bold in asserting free access to copyright materials if their intended use meets the current guidelines. They should become “copyright adults,” he said.

“You have to start practicing. People treat copyright law as something that is very, very complicated, very uncertain and indeterminate. Yes, the guidelines are not a checklist, but they they prompt us to ask relevant questions so we can then determine ourselves whether using works is reasonably necessary.”

Katz estimated most users are in the “early adulthood” phase of development when handling and copying copyright material. “They’re taking their first steps but they are still very confused and insecure.” Most haven’t had enough training or experience using the new process, and institutions are still developing techniques to take full advantage of the rules.

Some institutions are more mature as copyright adults than others. They are beginning to maneuver confidently through the guidelines to assert user rights. For instance U of T, among others, has abandoned global agreements for making copies. Instead the university is negotiating independently with rights holders, and looking for materials in the public domain to reduce costs and improve access to material.

Justice Binnie said a more restrictive system of what material may be used without charge wouldn’t do society much good.

"In so many of these copyright cases, they’re just pushing too hard. They’re trying to close down works that should be part of the public debate. It should be part of the commons. It shouldn’t be appropriated for the exclusive use of the copyright holder. We need a proper balance between creator and user rights.”

But three years after the pentalogy, finding that balance is becoming “a blood sport in a lot of ways”, according to another conference speaker, Casey Chisick, specialist and leader in intellectual property law at Cassel’s, Brock and Blackwell LLP in Toronto. In his practice, he advises both sides in the copyright equation, and he urged other lawyers to do the same.

“'Us versus them' doesn’t advance our understanding or the evolution of copyright law. It just distorts perspectives and gets in the way.” As Canada’s copyright process matures, Chisick sees “more litigation ahead and no doubt a host of new problems will present themselves”.

Justice Binnie, one of Canada’s most distinguished jurists and public servants, agrees. But he warns that anyone hoping for airtight copyright rules in the future is likely to be disappointed.

“There is no such thing as reaching safe harbour in copyright law because of the changing technology, the changing economics of publishing, the creators, the music industry; it’s all in disarray. So the court will have to keep reinventing and expanding the principles to keep up with the times. But I think the essential proposition is not going to change, this balance between the rights of the creators and the rights of the users. Beyond that everything is up for grabs. As it always has been.”